How do you acquire customers? It’s the most fundamental question for any business. You can have the best engineers, significant investment capital, or great culture but all of it means very little without customers and revenue. Every company will ultimately be judged on their ability to acquire customers efficiently. The ability to measure customer acquisition costs is crucial to understanding the viability of your business model.

Calculating Customer Acquisition Costs

Customer acquisition cost measures the amount of money it costs your business to acquire a single new customer. The formula for calculating CAC is:

CAC = Total Sales and Marketing Spend / Total New Customers

Seems pretty straightforward, right? Well, there’s a bit of nuance when calculating CAC.

What Period of Time?

First, define the period of time which you are trying to measure. Are you calculating CAC for the month, quarter, or year (or all three!)? Make sure that period of time corresponds to S&M spend and new customers in the desired period. If this is your first foray into tracking CAC, we recommend measuring sales and marketing expenses over the Trailing Twelve Months (TTM). This will help offset sales cycle timing which may create misleading metrics if you measured month-to-month.

What goes into Sales and Marketing Spend?

When you’re looking to calculate sales and marketing spend, it’s important to first take the time to properly structure your Chart of Accounts. If your sales and marketing accounts are set up appropriately, calculating CAC becomes much easier. Those accounts should include: salaries & wages for salespeople, commissions, advertising, travel, entertainment, marketing spend, creative and production costs for content development, and sales tools like CRMs and Reporting software. Essentially any cost that goes into acquiring a new customer.

New Customers

Another piece of the CAC equation is simply the number of new customers you signed over the desired period. This could potentially vary depending on how you define customers. For example, if you were selling seat licenses for your software, you’d need to define whether a new customer was a new company that started using your software or a new user started using your software within a company. In this example, the new company counts toward the CAC calculation, and additional seat licenses would be tracked by your customer success teams as an upsell but not captured in CAC. Speaking of customer success…

The Customer Success Debate

When you think about sales and marketing costs, generally you think about spend focused on generating new business. In many SaaS companies, however, customer success departments focus on “landing and expanding” via upsells and cross-sells. This can obviously result in significant increases in topline revenue. So is it a “sales and marketing” activity? As with any good question, the answer is, it depends!

Building this formula obviously depends on the type of business you are and your level of sophistication in building KPIs. If you are an advanced SaaS company, you’d likely break out new bookings and expansionary revenue as two different metrics. Ultimately, you’d separate your Customer Success costs out of the CAC calculation, creating multiple metrics to track the cost of your upsell, cross-sale, and renewal revenue.

For those just starting out or with long implementation cycles, we’d recommend baking in Customer Success costs into your CAC calculation. First, it’s much easier to total up all of your sales-related costs versus identifying which dollars came from new bookings and expansionary revenue. Another reason is that Customer Success or Implementation is likely part of your sales cycle and process. Recurring revenue is not likely coming day one of signing a contract. So depending on how you onboard clients, customer success, account managers, implementation specialists, etc. are likely all part of the process of gaining a new customer. Essentially you would be adding up all of the costs up to the moment you invoice them the first time. This keeps CAC simple and tied to real revenue versus paper contracts.

This is our recommendation for companies just starting out developing their KPIs. Obviously, as things get more sophisticated, customer success costs can ultimately be broken out of CAC to better understand how revenue is derived.

CAC Example

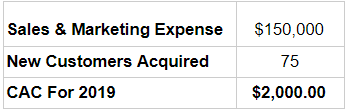

Assume all of your sales and marketing spend for 2019 totaled $150k. For that spend, you acquired 75 new customers.

So essentially you know that for every $2,000 you spend in sales and marketing, you can predict that you will onboard a single, new customer. Good to know!

But in a vacuum that doesn’t really tell us much. If the average contract value for a customer is $10,000 that’s really good, if it’s $100, not so much! Which is why CAC is almost always associated with the Lifetime Value (LTV) of your customers. In our next post, we’ll deep dive into LTV and how it’s calculated to ultimately understand your CAC:LTV ratio or whether or not your business is viable.

CAC Payback Period

Another way to gauge the effectiveness of your customer acquisition spend is the CAC Payback Period. Simply, the formula is:

Payback Period = CAC/Average MRR per customer

Using our previous example, CAC is $2,000 and we will assume the average customer revenue is $350/month. The payback period, or the time it takes to recoup our sales and marketing costs necessary to acquire a new customer is 5.7 months ($2,000/$350).

This tells us that, before even factoring in our cost of product/service delivery, it will take 5.7 months to recoup our investment in the Sales & Marketing efforts that were expended to obtain that customer. Once again, this can be good or bad depending on how long that customer stays with you.

LTV is Next

Now that we’ve done a deep dive into understanding Customer Acquisition Costs, our next post will break down the Lifetime Value of your customers in order to build towards a CAC:LTV ratio and benchmarks for your business. Stay tuned!